A few days ago, countless investors were disappointed when Jet Blue’s (NASDAQ:JBLU) attempt to buy Spirit Airlines (NYSE:SAVE) was thwarted in federal court.

I certainly haven’t read the whole ruling — and don’t intend to — but here’s the gist of it. The judge agreed with the U.S. Department of Justice’s assertion that letting the two airlines combine would ultimately hurt consumers by having one less competitor in the market.

Spirit’s shares crashed hard on the news, falling as much as 50% when the ruling was announced. Shares did recover as the day went on, but still closed down 24% lower.

The interesting thing about this deal was the sheer mass of retail investors playing the situation. Led by some prominent names on Financial Twitter (Fintwit, for those of you not familiar with the lingo), who were actively bullish on the deal closing in Spirit’s favour, it seems like thousands of retail investors lost big by betting on the wrong outcome. I saw a couple of investors say they lost at least “six figures” on this arbitrage, but I always take claims like that with a grain of salt. After all, you can say most anything on Twitter without much consequence.

I’ve done a bunch of merger arbitrages over the years, and when the deal was squashed I decided to share a very condensed version of my special situation rules on Twitter. The post did pretty well:

I got a decent amount of new followers and engagement on the tweet, with more than a few people accusing me of jumping on exactly at the wrong moment, as if I had this planned for the minute the Jet Blue/Spirit deal was squashed.

That was disappointing, since I’ve done dozens of these deals over the years. I consider myself a pretty good arbitrageur, and have had success at it. So I decided to put my proverbial pen to paper and publish this completely free guide to how I play merger arbitrage, odd lot tenders, and other special situations, and expand further on those rules that have saved me from so many poor deals in the past.

I would appreciate if anyone who found this useful would also subscribe to my free newsletter, investing wisdom delivered to your inbox each and every Sunday morning. It’ll make you a better investor, guaranteed.

Let’s start first with some definitions.

What’s a special situation, anyway?

(Feel free to skip this section if you’re already well familiar with the lingo and how these situations arise)

Let’s start at the beginning. What exactly is arbitrage, anyway?

The classical definition of arbitrage is the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same asset in different markets in order to profit from a difference in its price.

A simple example would if gold traded at $1,000 per ounce in London and $1,010 in Paris, once you factored in exchange rates. An arbitrageur would buy the gold in London, immediately sell it in Paris, and pocket his $10 profit. Since this is a risk-free profit, a rational investor would continue to do this trade until the inefficiency closed, even going as far as borrowing money to leverage the situation.

These kinds of things happened much more commonly in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, times when information was not so readily available. There are some famous stories about the Rothschilds realizing speed of information was huge and employing a horse relay system so they could get information a few hours before everyone else, a massive advantage that seems really quaint today.

These days, of course, information is available to everyone all at the same time, and there’s no advantage left over for anyone — although folks strongly opposed to high-speed trading would disagree with that point. So the definition of arbitrage has changed.

These days, most arbitrage is in the form of risk arbitrage, where an investor analyzes the risk in a special situation in the market and determines whether the implied risk is above or below the actual risk. Don’t worry right now if that sounds complicated, we’ll get to some examples in a minute.

These risk arbitrage special situations are essentially divided into three groups:

- Merger arbitrage – where investors bet on the likelihood of a merger, acquisition, or take-private transaction happening or not happening

- Odd lot arbitrage – companies doing large share repurchases (called standard issuer bids, or SIBs) will often leave a provision where shareholders who own odd lots (less than 100 shares) can tender their shares without proration. This creates an opportunity to profit, although that opportunity is quite limited

- Convertible arbitrage – leveraging the inefficiencies between convertible bonds and the underlying stock. For example, a convertible bond trading for $100 is convertible to four shares of stock. The stock trades for $30. You’d buy the bond, convert it to shares, and immediately sell the shares for $30, pocketing your $5.

Note, your author has never been able to find any convertible arbitrage situations that tickle his fancy, so this piece will focus on the first two types of arbitrage. You also need a certain amount of knowledge of convertible debentures to succeed at convertible arbitrage, something I don’t have and won’t likely acquire.

Next, let’s talk about how to find these special situations.

How to find arbitrage situations

So you’ve read all about arbitrage (or you already knew what it was), and you’re still eager to make some profits. Okay, great. So let’s begin by talking about how to find these situations.

I’ve found all of these to be effective over the years, although they do come with downfalls.

We’ll talk about the laziest way first. You just live your life just like normal and sort of stumble upon these special situations. You read about it on Twitter, or see a headline on BNN or CNBC, or find out about it in some other way. This has the advantage of being really easy — ridiculously easy — but has one massive disadvantage. You’ll limit yourself to the biggest and most public deals this way, which I think is pretty much the opposite of what you want to be targeting.

The next laziest way is to simply pay someone to track all the mergers, acquisitions, take private deals, odd lot tenders, and so on. There are a few of these services out there, most with very reasonable fees and pretty smart people looking at these deals. They almost always offer a certain level of analysis too, which is a nice way to get up to speed. But the analysis is both good and bad, since many people will take the lazy way out and simply copy what the author suggests. That leads to crowded situations, and those can turn out very badly.

Finally, I’ll share my preferred way to find these special situations — Google Alerts.

My strategy here is very simple. I set up Google Alerts for all the important keywords and have them set up to hit my inbox each day. Phrases I use include:

- Odd lot

- Take private

- Substantial issuer bid

The secret to using Google Alerts is you have to be a little more specific. You can’t use something like “merger” or “arbitrage” because they’re too generic and you’ll be wading through mountains of useless junk. But you can also be too specific. Ultimately, what you want is to be made aware of a steady flow of these special situations, covering everything from the big deals that make all the headlines to the smaller deals that only get published in trade journals, local news, or more obscure sources. In this game the more rocks you can turn over, the better.

Canadian investors can also use SEDAR+, the much maligned electronic filing system for Canadian securities reporting. The old version of SEDAR was very easy — you could pop in once a month or so, do a search for the document type you wanted, and Bob’s your uncle. The new SEDAR is weird and unusual, but I think I’ve figured it out. At least partly.

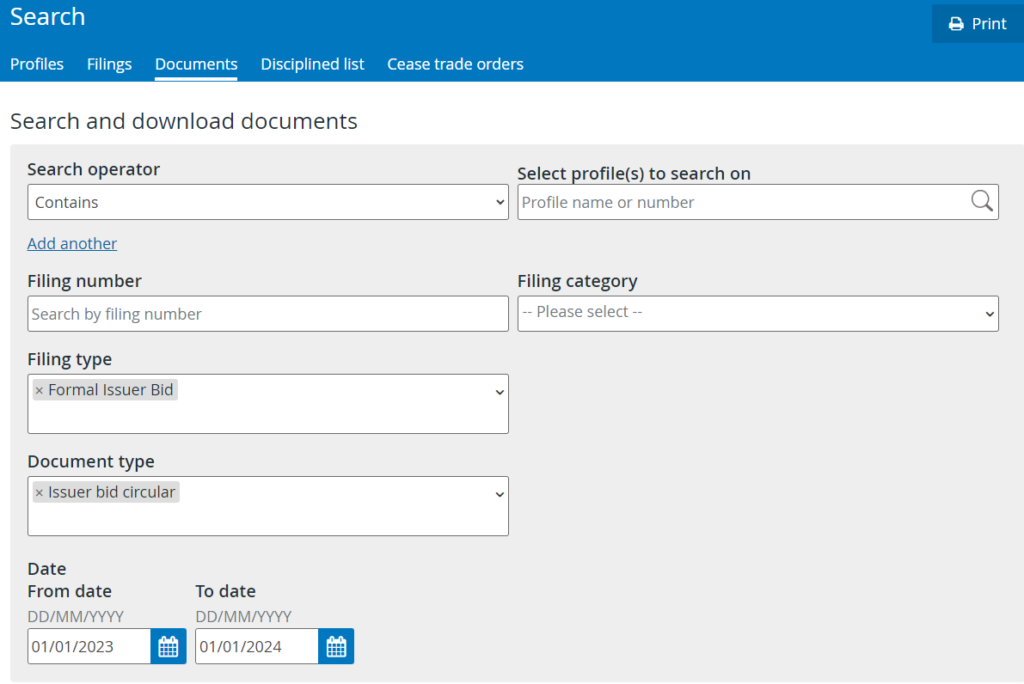

To search for SIBs, choose Formal Issuer Bid and then Issuer Bid Circular, like in the screenshot below:

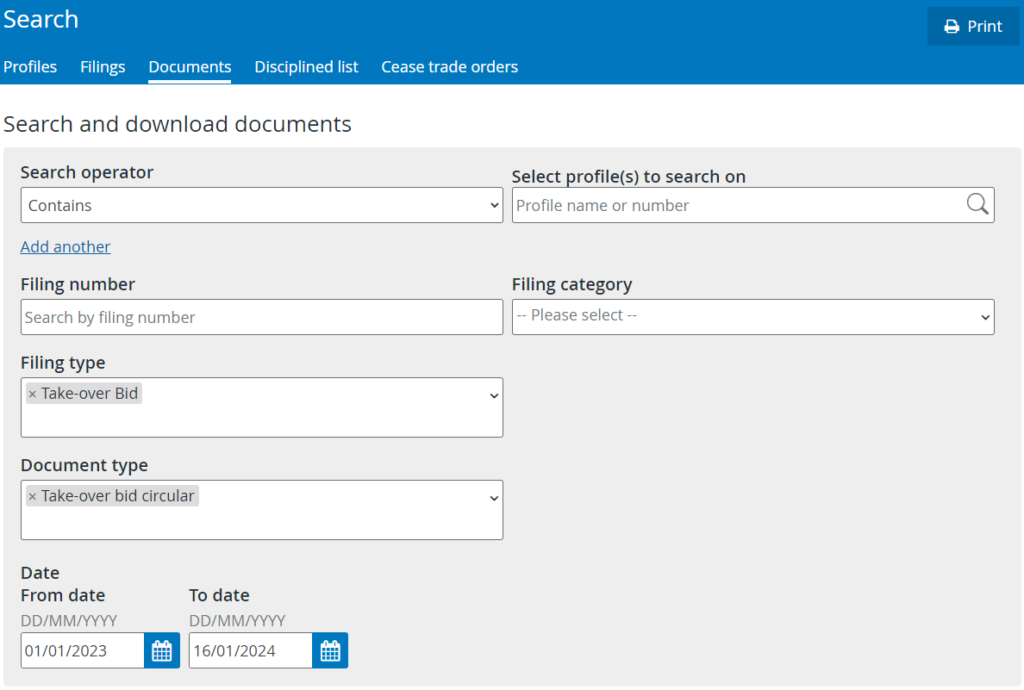

To look at take-overs, you want to put in “take-over bid” in filing type and “take-over bid circular” in the document type.

That way looks for takeovers from non-controlling shareholders or competing companies. Unfortunately, I don’t know how to use the new version of SEDAR to effectively look for takeovers from controlling shareholders (which is a VERY fertile hunting ground), so I can’t offer directions on that. If someone knows how or knows of a resource telling you how, I’d be much obliged.

The majority of these deals are in the U.S., and your Google Alerts should pick up most anyway.

How I play odd-lot tenders

I effectively view odd-lot tenders and merger arbitrage as completely different things, even if they’re both in the arbitrage category.

I’m also putting this first because the vast majority of my efforts in the arbitrage space go towards odd-lot tenders. At least 80% of my efforts go into odd lots these days. I find them to be much simpler than merger arbitrage, a space crowded with professional investors.

To review, an odd-lot tender is a situation where a company is repurchasing a big block of their shares. To make it fair, the company will announce to all shareholders what it plans to do and what price it will pay, so all shareholders can participate. But it gives shareholders who hold less than 100 shares (odd-lot holders) special priority.

The announced price will either be a set price or a range.

Let’s look at a fictional example: Nelson Co has 10M shares outstanding at $20 per share. The company announces it’s going to repurchase 2M shares at a range of $22 to $25, with an odd-lot exception.

Nelson Co shareholders decide to bail (jerks) and 5M shares are tendered to the offer. Since the company only offered to repurchase 2M shares, each shareholder gets pro-rated, meaning, at least in this scenario, they only get 40% of their offered shares purchased.

The odd-lot provision, meanwhile, means that anyone who tenders fewer than 100 shares is not subject to proration. They get all of their shares purchased no matter what happens with the rest of the deal. This then further pro-rates things for the rest of shareholders, who end up with somewhere under 40% of their shares tendered.

So the arbitrage situation here is pretty simple. You wait for the announcement, buy up 99 shares, and tender those bad boys. Easy. Peasy. Lemon squeasy.

Don’t just rush into a situation, either. Often, when a company announces a SIB, shares will rocket very close to the offered price as arbitrageurs bid up the stock to get their piece of the pie. If you patiently wait and buy a little while later, you’ll often get a better price. I’m willing to buy up to a week before the offer expires. Any closer to that and I start to worry I won’t be able to do the tender process in time.

In theory, you should be able to buy two days before and tender your shares the day before and you should be fine. I like to give myself a little more time, as a just in case scenario.

The problem with odd-lot tenders

On the surface, odd-lot tenders look like a free lunch, something we all know is impossible in the finance world. You buy 99 shares of something and sell it in 4-8 weeks back to a buyer who has said they’re going to buy your shares. As long as you buy in for below the offer price, the profits are guaranteed.

Ah, not so fast, compadre. There are a few problems. Sometimes, companies will just change the rules halfway through — which, by the way, is perfectly legal. An SIB is not a contract; it’s an offer to buy, and you should treat it as such.

In 2018, Blue Bird (NASDAQ) offered to buy approximately 7% of its outstanding shares for $28. The stock traded at the $25 level. Arbitragers crowded in, buying 99 shares to take advantage of the odd lot exception, which hit a bit of a frenzy when Seeking Alpha published a piece on the strategy.

It didn’t help the author called it a “free lunch”, either.

Suddenly, a couple weeks before the deal was scheduled to close, Blue Bird announced it was dropping the odd lot preference, meaning investors with fewer than 100 shares were in the same boat as everyone else. They no longer got preferential treatment. The stock fell 25%+ in the next month as the arbitrageurs rushed for the exits. The company, meanwhile, was happy — after all, they got their allotted shares at the amount they were willing to pay, all while screwing the arbitrageurs.

Your author remembers this well because he participated and lost money. I did better than most, patiently holding my shares for a couple months to cut my losses to about 10%.

The other big problem with odd-lot tenders is they don’t scale. If you buy 99 shares of a company worth $50 that’s offered to buyback shares at $55, you’ve got a maximum profit of $495. In a good year you might do 12-15 of these deals; in a bad year it could be as few as 3-5. And take it from a guy with experience in this part of the arbitrage world — $500 is a decent profit. I’ve done ones as small as a $200 profit and don’t generally touch anything smaller than that.

Now there is a way to scale this strategy, at least a little bit. You can odd-lot tender the same deal in different brokerage accounts and nobody is the wiser. For instance, you can:

- Buy 99 shares in your account, pocket $495

- Buy 99 shares in your spouse’s account, pocket $495

- Buy 99 shares in your son’s account, pocket $495

- Buy 99 shares in your daughter’s account, pocket $495

You get the idea.

There are even people who maintain, say, an RRSP account in one brokerage and a TFSA account in another brokerage and will do the odd-lot tender in both accounts. That is, as far as I know, against the rules, since each individual shareholder is limited to the 99 share odd-lot provision. However, I also know people who have gotten away with it.

My rule of thumb is to not abuse these situations, since I know companies can go in and cancel the odd lot provision whenever they’d like. If too many people go to town on these situations it ruins it for the rest of us.

How to tender your shares

Okay, you’ve got your 99 shares and you’d like to sell them back to the company. How do you do that?

What you need to do is to instruct your broker that you’d like to participate in the tender offer.

Different brokerages have different ways of going about this. Some have a nice handy online form you fill out, meaning you don’t have to talk to a person on the phone. Questrade and Interactive Brokers offer this. Tell the form the stock you want to sell, the price, and the number of shares, and someone processes it on the back end.

Other brokerages — like Qtrade, which I know for sure because I use Qtrade — make you phone in. This can be frustrating in a number of ways. First you have to navigate the phone menu, then wait on hold, then, when you finally talk to a person, they sometimes don’t even know what’s going on. To Qtrade’s credit, however, the last few times I called in they were great.

I’ve had tenders where I had to tell the brokerage employee where to find the info on the tender offer online, and then walk him through the terms.

You then spend 5-10 minutes on the phone with the rep explaining everything and confirming everything on their end.

The process is the same if you’re tendering your shares in an acquisition scenario. And there’s no cost to doing so.

If you’re unsure of how to tender shares with your brokerage, there are two ways to find out:

- Google “[your brokerage] tender offer” and instructions should pop up

- Contact your brokerage (or use the many help documents they have on their website) and find out

Typically you’ll have 6-8 weeks from when the company announces the SIB to when it actually buys back the shares. What I do is wait until we’re getting close to the day the transaction actually takes place, say 5-10 business days before. This allows the brokerage time to iron out the kinks on their back end, and you’ll have better visibility into what the deal will look like, especially useful in a situation where the company has told you a range they’re willing to pay.

You also have the option to sell your shares in the market. Say you bought something for $50, intending to sell it for $55. For whatever reason, the stock hits $57. You’re free to sell your shares at that point, even if you’ve instructed your broker to tender. It just has to be before the expiry day. So if a tender offer is for December 31st, you can sell your shares on December 30th.

Once the company has repurchased your shares, they’ll remain in your account for at least a few business days while your broker sorts everything out and the money moves around. Do not try to sell your shares in the open market in this scenario, although I don’t think your broker would let you do so anyway.

Merger arbitrage

Merger arbitrage is a lot more complex than odd-lot arbitrage, and therefore I spend most of my time on the latter. But merger arbitrage can be a fertile hunting ground, provided you follow my ground rules.

Essentially, merger arbitrage takes on the following forms:

- An all-stock merger of two equals

- One company acquiring another for cash

- One company acquiring another for stock

- One company acquiring another for a combination of stock and cash

- Private equity or another private owner acquiring a company

- A minority shareholder taking a company private

- A majority shareholder taking a company private

There are a million more combinations, but those are the main ones.

In a given year there are anywhere from a couple dozen to hundreds of acquisitions in North America, with even more around the world if you’re willing to play there. The hunting ground is fertile, and investors who venture into this part of the market need to be patient.

At its core, most people think merger arbitrage is about odds. You’re looking for situations where the odds of a deal happening are greater than the implied odds.

For example: Nelson Co decides to acquire CDI Inc for $10 per share. CDI shares go from $5 to $9.50, suggesting that there’s a 10% chance Nelson Co won’t go through on the deal ($0.50 upside, $5 downside). You read all the offering documents, do research into Nelson Co, and conclude there’s a 95% chance the deal closes. The real odds exceed the implied odds, so it’s a good arbitrage situation.

But I don’t think you should look at merger arbitrage like that — for a couple reasons. For example, say Nelson Co’s offer to buy CDI Inc. only resulted in CDI shares rising to $8. That concludes there’s a 40% chance ($2 worth of upside, $5 worth of downside) the deal won’t go through. You read all about it and conclude there’s a 95% chance the deal closes.

If you’re playing this from an odds perspective, you’d put a huge amount of your portfolio into this. You have a 95% chance of a 40% return and a 5% chance of a -50% return. Those are great odds, and if you do enough of them you’ll get rich.

There’s just one problem — in that situation the merger arbitrageur is almost always underestimating the risk involved. It’s not a 95% chance of a 40% return; it’s more like a 50/50 bet.

You’ll often see the same thing happen. An investor will play a couple of merger arbitrages with huge spreads and be successful at it. So it emboldens him and he bets more and more. By the third or fourth one the odds catch up to him and it’s a disaster.

The way to be successful at merger arbitrage is to stop thinking about it as an odds based exercise. That thought process will lead one down a path where they’re essentially gambling, convinced they have some sort of edge in an area where they don’t. This is exactly what went wrong with the Jet Blue/Spirit deal.

Instead, remember what arbitraging is at its heart: a risk free transaction where you’re simultaneously buying and selling and taking a small, risk-free profit for doing so.

Ladies and gentlemen — the rules

It is with this in mind I created the rules demonstrated in that tweet so many words ago. To remind everyone, they are:

- Avoid huge spreads. The market is telling you something.

- Avoid big publicity cases

- Don’t own anything you wouldn’t own if the whole deal went south

Many people in the replies thought a potential merger arbitrage was a no-go if it broke all of the rules. Let me clarify right now — a merger or acquisition is a no-go if it just violates one of the rules.

What the rules do is force you to operate in very specific situations. Specifically, you’re looking for:

- All cash deals

- From friendly buyers or, even better, controlling shareholders

- With very few conditions

We’re looking for simple deals in forgotten corners of the market. They say arbitrage is picking up nickels in front of a steamroller; if you’re selective enough you can minimize the risk to picking up quarters in front of golf carts. It still sucks when the deal goes sideways, but you can bounce back a lot easier.

Simplicity is the key here, and every condition the buyer must meet increases the chances of a deal going sideways. A few conditions — especially when the government gets involved — turns a merger arbitrage into merger gambling. It’s basically a parlay, and gambling houses love offering parlays. They increase the chances of loss.

When you look at an arbitrage situation strictly by the odds, it becomes gambling very quickly — even if you have an edge (spoiler alert: you don’t). Arbitrage is the risk-free leveraging of one market against another. No acquisition is risk free, but you can minimize your risks by sticking to situations that are as close to risk free as possible.

But Nelson! That’ll decrease the number of deals I can play. Yup. In fact, that’s the whole point.

The bottom line

Thanks for making it all the way to the bottom. Hope I was able to teach you something.

With so many investors discovering these types of special situations, it’s become a crowded market. Your author participated in an odd-lot situation a couple of months ago that was virtually all arbitrageurs. This worries me. To be completely honest if I ran a company and I was doing a big share buyback, I’m not sure I’d include an odd-lot provision. They’ve become very crowded trades.

I’ve taken a break from doing these, in fact.

But every time I would talk about these on Twitter, I’d get some interest. So now, instead of answering questions, I can just point people here.

And please, if you found this valuable, I’d appreciate it if y’all would subscribe to my free newsletter.